Thoughts on the Capstone Process

Mark Bristol is a highly skilled storyboard artist and director. He’s worked in television, film, and the video game industry. After listening to a demo CD of mine, he hired me to score music for a short war re-enactment film featuring soldiers fighting on the Pacific front in World War II.

Later on, he reached out to me again with a different, more intimate sort of film titled Countdown. It’s also a short, and features a bleak situation in which two people are faced with a finite, steadily dwindling source of food and water. It’s a powerful story, and spoke to me strongly. Unfortunately, at the time other pressures and conflicts pulled me from school and composing, and I had to put completion of my degree on hold. When I was able to return, I quickly returned to Countdown as well, and its completed soundtrack ultimately became my Capstone.

Last year, I committed a final score to paper, then transferred it to Finale, a music notation program, to fully flesh out the orchestration. Pro Tools, Kontakt, and EastWest then served in the creation of a MIDI mockup. After tweaking a few things based on valuable feedback from Professors Gary Hickinbotham and Mark Erickson, and after getting Mark Bristol’s go-ahead as well, I returned to Finale to make final adjustments to the score, then prepared all of the individual instrument parts. With that done, it was time to move forward.

Finding players happened in stages, since it took half a dozen sessions, spread out over months of time, to swap every MIDI part out with real performances. I spent a lot of time at Texas State’s music building, and found that the very best way to get players interested was to walk up and engage them one on one. To that end, I mingled with performers after concerts, knocked on practice room doors, and randomly introduced myself to people carrying the right instrument cases. (I found my solo cellist on the stairs between the first and second floor of the music building that way, for example.)

I found every one of the brass players by showing up during their band auditions, while they were waiting outside in the hallway for their turn to go in. The string players, more than the others, took more working on. I went to multiple Texas State Symphony Orchestra rehearsals, showing up ten minutes beforehand to chat with players as they set up their instruments. The conductor, Dr. Watson, twice allowed me a few moments at the start of rehearsal to announce myself and to pass out pamphlets. I was allowed to briefly address a few different string studios during their weekly meetings, passing out pamphlets there too, and also spoke at one of TSU’s String Project meetings. All of this, combined with seeing my face frequently in the music building, seemed to give many players the last little push they needed to actively commit.

Here is an early example of one of many handouts, which got progressively simpler and smaller. The session noted here didn't come together as planned:

_____

My first recording session included most of the soloists: flute, clarinet, violin, cello, bass clarinet, and bassoon. The second session focused on brass players; a mix of trumpets and French horns. The third session included the string section, which ultimately led to a follow-up session to overdub more cello. I handled the piano part, which was recorded using the grand piano in the A room. I’m grateful to Armando Pinales, a fellow SRT student, who helped with set-up and tear-down, and manned the session during recording. Without his help, the session would have been much more tedious. I also hadn’t practiced the piano part enough, which meant we needed multiple takes to get things right. It was a humbling reminder that each part of music production requires wearing a different hat, so to speak. Composing the music, finding musicians, preparing for and managing the session as the recording engineer, directing the ensemble, mixing the music, and sitting behind the microphone as a performer all entail a unique skill set, and deserve separate, focused preparation time.

The final recording session featured solo harp. I had a long delay in finding a harpist (there is no harp program at TSU right now), and ultimately, when even students at UT Austin were scarce, Delaine Fedson, professor of harp at UT, made herself available to me. She, along with the solo violinist, were hired on as paid studio musicians, rather than as student volunteers. In working with Delaine, I got a taste of how the dynamic changes when you are working with an industry professional with many years of experience, versus students who are volunteering their time and for the most part have never been in a studio. The harp session was fast and efficient, with the load-in and load-out of the harp itself being, by far, the most difficult part, given that it had to make a journey upstairs. (Thank you for the added man power, Professor Erickson!)

I enjoyed every recording session, and am thankful to everyone who participated. I hope to work with many of these wonderful players again in the future, on a paid basis, because cookies are tasty, but skilled performers deserve a paycheck!

Session Setup Decisions and Issues

Given that this music called for classically trained musicians, my goal was to create as natural of an ensemble setup in each session as possible. I was certain that everyone's performances would improve if they were able to read and respond to each other in the same physical space. I also love the way each individual’s sound will intermingle with the others when in a shared space, and wanted the opportunity to capture that as well. Given the space constraints, along with the inverse relationship between the number of musicians and the ease of successfully booking a time that worked for everybody, I ended up having about twice as many sessions as originally planned. For example, initially I planned to record harp and piano with the other soloists, which would have allowed everyone to play off of each other more naturally. It also would have provided a nearly complete framework for the string and brass section players in subsequent sessions. Instead, the first session relied heavily on a MIDI mockup of the music, along with my conducting, given that there were many gaps of time in which no one in the session was playing. Each subsequent session utilized an ever evolving compilation of MIDI mixed with prior session recordings.

That said, even with many sessions being necessary, after a lot of massaging in post production, the result still feels like a proper ensemble performance. That is because, for every session, regardless of the ensemble size, I consistently placed two sets of room microphones in the same locations. I also placed the musicians (with some overlap due to the room size) in their relative positions based on a traditional orchestral layout. The recording is from an audience perspective, with high strings to the left, low strings to the right, etc. Invariably, the predominant sound you hear in the mix, for every instrument except possibly for brass, is the “room” sound, which is a blend between the room microphones: a spaced pair of AT4050s, and a pair of Royer 122s in a Blumlein configuration.

Each soloist also had one to two close microphones, and each pair of string players in the string section shared a microphone. Brass also shared microphones in pairs, except for one brief phrase of music that called for a single French horn, which was overdubbed with the horn player more centered on the mic. The piano and harp, between them, had over a dozen microphones, some of which I didn’t use (for example, a pair of Fatheads placed a foot above the piano strings, and a foot back from the hammers, which was meant for a darker sound, didn’t make the cut.)

For the harp, in particular, I learned that more space is essential to the sound; a microphone set too close doesn’t capture the interaction between the strings in a way that sounds natural to the ear (although getting really close in could be just the thing if you were going for something like a cross between piano and prepared piano, with less hammer strike and metal to the tone - particularly in the extremely low register.)

A lot of post production work was needed to bring everything together. In writing the music, I had kept the difficulty level in mind, and believed the music to be, generally, sight readable material. That said, the tempo subtly changes nearly continually, and shifts suddenly at points. The music is slower and in an easier key, even for the transposing instruments, but given its somewhat rubato nature, I clearly underestimated the time we would need to come together as an ensemble. To everyone’s credit, most players had taken the time to print out and look over their parts before the session (I also had printouts for them as needed), but I had made the decision to dedicate the first few hours of each recording session (up until the last few sessions) to group rehearsal, rather than trying to schedule it at a different place and time. Also, most of the players, as students, are still in the midst of building skill on their instruments, and are used to a highly trained, skilled conductor at the helm. (Alas, they had me, instead.) With each session, my conducting became cleaner and easier to follow, but it wasn’t ideal for the players.

Given these factors (and, in retrospect, mistakes in judgment and preparation on my part), I had to extensively edit every recording. No part of the final mix consists of a single take. In fact, very nearly every phrase in every section is a compilation of multiple takes, even the solos. I was very hands on; I shaped dynamics, shaped sound with EQ, and trimmed note lengths. I even spliced, in many cases, single notes partway through, to compile a performance that resulted in the phrasing and timing I needed. To be clear, it isn't that I felt obsessively compelled to exactly match the real performances to the original MIDI timing. It's awesome when anyone puts in time and effort to learn something I've written, and a skilled player's performance is always a joy, partly because of the additional layer of spontaneous, creative energy they pour into the music. I would have been happy to leave the performances mostly as they were, in regard to timing, at least. In this case, however, I had to match the music precisely to the film. In particular, there were several clean cuts from one scene to the next without a cross dissolve or something like it to allow for wiggle room with the musical timing. Also, since Countdown is a completely silent film, the music is always front and center.

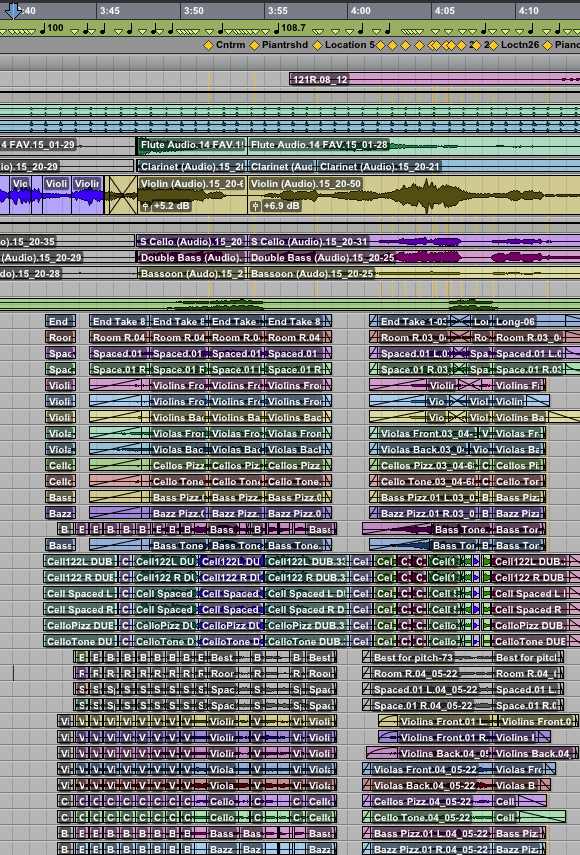

Here's an earlier snapshot of a Pro Tools session focused on the string section mix, which shows about twenty-five seconds of music:

I also, at points, in limited ways (mostly to fix the occasional wrong note), mixed and matched the higher and lower strings from multiple takes. I also doubled the strings at points where I wanted a larger sound. With the solo violin, in particular, I used quite a lot of EQ on the close microphone, which had picked up a particularly harsh tone, and no warmth. Without the room microphones, the tonal shaping in the violin would be blatantly obvious to anyone’s ear, trained or not, but once combined, the sound is much softer, and closer to what the piece calls for. The violin’s close mic sits decidedly underneath the room microphones in volume, much like a limited drum submix might sit under less compressed drums. The close mic lends more stability to the violin’s presence, although, as is typical with orchestral music, no compression of any sort was used during the mixing (or recording) process. Professor Erickson also suggested applying a chorus effect plugin, which further softened the close mic’s tone.

Tuning was another interesting puzzle. I found that EQ helped here, too. When a pair of instruments were slightly jarring when set against one another, but not necessarily glaringly out of tune individually, I would, sparingly, automate EQ at points to affect a change on particular notes. I used this with clarinet at a few points, to soften its interaction with the violin, for example. I also found that certain microphones would pick up the sound differently in regard to pitch; in particular, the solo cello’s two close microphones, when blended a certain way, helped obscure a few pitch issues, but with just one microphone, the problems were exacerbated. That said, there were places where the pitch absolutely had to be corrected, and Melodyne was my tool of choice. Given my use of room microphones, I could never correct just one track, so fixing a pitch always required multiple tracks. Depending on what needed correcting, I would end up fixing quite a few tracks; for example, flute and clarinet and violin all had enough bleed between them that fixing one meant altering the others, too, to some extent, plus the room mics. I struggled, especially early on, with the way in which the tonal quality, even with subtle pitch changes, would also change. Ultimately, however, I used Melodyne at many points in the piece, because after stepping back and objectively evaluating it, there was no question that the tonal shifts were more subtle than a note that was noticeably out of tune.

Ultimately, the entire editing and mixing process, in regard to timing, dynamics, pitch, tone, etc, all boiled down to creating a mirage of sorts. In other words, as the mixing engineer, I continually ask the listener to focus on one thing while disregarding another. It’s fascinating to compare the original takes with the final mix; the contrast is stark, because so much was altered in some form or another. That said, even from the start, I loved the studio recordings. MIDI mockups, even with excellent orchestral plugins, don’t hold a candle to an ensemble of musicians breathing energy and skill and emotion into a real performance of the music. Even listening to the raw, unedited string section takes put an involuntary grin on my face. Issues aside, it was a magical thing.

Get the foundation right.

I truly, finally took home the lesson that the initial material you obtain during the session is like gold. This is hardly a new idea; I’ve heard this over and over again in class. I’ve experienced plenty of post-production pain after recording rock bands and fellow SRT students. But until the capstone, it never hit home in such a powerful way.

I’ve finally learned this lesson, though. There is no substitute for, as Gary Hickinbotham likes to say, a solid foundation. With that in place, the time spent on editing, mixing, overdubs - all aspects of post production - is drastically minimized. The best practices used in the pre-Autotune, pre-digital editing era ought to be the gold standard when it comes to studio recording: prepare thoroughly, get incredible takes, and have most of your editing already complete before the musicians are walking out the studio door. I never quite appreciated just how valuable it is to be in a position where your mixing work, after having utilized proper microphone placement, and with solid performances at hand, can and should be a matter of tweaking things, rather than using Pro Tools to dismantle and reassemble it all from the ground up, as I had to do with this piece.

It’s great to have a bag of post production tricks, but ideally, particularly with orchestral music, I shouldn’t need to use them. For example, the solo violin’s tone on the close mic was my fault, because if I had taken the time to really listen and make sure the tone in that specific microphone was solid, I wouldn’t have needed to drastically warp it with EQ later on. Instead, I should have moved the microphone until I either got the tone I wanted, added a second microphone, or swapped it with something else (a Royer 121, in retrospect, would have captured the softer, darker undertones of the instrument, while the surprisingly bright AKG C414 I had borrowed from another SRT student could have been used subtly to add detail.)

Microphone choice and placement is a specialty in and of itself. I am far from proficient, but I’ve learned to trust my ears during my time as a student in the SRT program. I’ve gained a healthy appreciation for just how much skill some people in this field have acquired over years of trial and error during their on-the-job experiences. As I progress, my goal will be to be more mindful of every step in the process, and to always remember the basics. Foundation first!

Have Confidence and Communicate Clearly

This taught me so much about how to work with different players, in regard to microphone choice and setup, physical space requirements…the nuts and bolts of what worked, and what didn’t work. But maybe most importantly, I learned a lot of about how to communicate better, and that my own attitude around the people I work with broadcasts confidence, or uncertainty; calm, or agitation; joy, or worry…and that all of these impact the performance I’ll be able to coax from these perceptive, attentive individuals.

There are nuts and bolts to communication, too. A way to reach out, to run a session, to maintain rapport, to follow up afterward. People have methods and styles they develop, but certain universals are present with professionals; do's and don’ts of behavior.

In the first session, featuring the soloists, for example, I didn’t broadcast the level of confidence you would expect from someone who has composed the music, organized the players, booked the time, and set up the session. I came across as, in retrospect, overly self deprecating, which can be a camouflage for fear. Fear is never good; people can smell it! One of the players began to end phrases later, or stop a little earlier, than the rest. At the time, I could tell there was a friction there, something in how we were jiving that drove him to slightly misstep, as if he couldn’t trust my conducting. The others were on; I’m sure it was my attitude, because I was in the position to firmly (but gently) assert control. It’s what everyone expected, as well. I created the issue by not being firmer and more confident in my approach.

It took a lot of introspection (and time spent editing takes that didn’t line up right), to acknowledge the power our daily communication with others has, in regard to potential work, and overall career trajectory.

Budget Time Just Like You Budget Money…Have a Buffer.

It always takes longer than you anticipate. Finding interested players, then finding new players when some musicians remember about a prior commitment…to later on find last minute players when someone suddenly drops out (I owe a huge thank you to the head of TSU’s violin department, Lynn Ledbetter, for recommending an alternate solo violinist to me the day before that first session). Or, somebody gets a flat tire the day of, and can’t make it (this happened). Sometimes people simply don’t show up, and don’t tell you they won’t be there; the string section recording happened in two sessions (and ultimately required a little beefing up with MIDI strings laid in underneath at points,) for that reason.

Finding times to rehearse and record that work for everyone, particularly with volunteer musicians, became less easy with each additional person I added to a session. During the course of preparing for these sessions, I learned to pay attention to every available announcement regarding ensemble performances, holidays, special events, and how to ask the right kind of questions to get information from students whose job, understandably, isn’t to warn me about potential future conflicts. That was my job. I also learned how things change when you are working with paid musicians; the answer, not as much as you’d think. They are easier to reach, and are better about reaching you back, but organizing multiple people to meet at the same place and the same time is still a time consuming process.

Then there was editing and mixing, after the sessions were complete. And that goes back to the first big lesson: get a good recording, because otherwise post production will take a lot, lot, lot of time, which it did.

Be organized, because someday, someone will want a project from ten years back.

Admittedly, this lesson comes to me in many forms. It’s a continual battle. Being organized is unintuitive to me (I tend toward extreme spontaneity) but building a consistent approach to everything is absolutely necessary, from my Pro Tools session layouts to how I gather and organize session musicians. I created problems for myself, and later solved them, simply by being more mindful. How I kept track of musicians is a good example: initially, I haphazardly took down an email or phone number (whatever the person offered) and sometimes on paper rather than on my phone. Later on, I methodically obtained everybody’s email, first and last name and, if I could get it, their phone number as well, then immediately added them to the appropriate group in my contacts list on the phone, which then saved to iCloud, providing local and remote storage.

Within Pro Tools (and other music editing software), organizing tracks by type, color coding them, routing things logically (both Gary and Chris helped me there), creating groups to edit sets of instruments efficiently, using VCA tracks to affect level without altering effects…these are life savers. Maybe this seems logical to most, but simply defining an order in which to complete tasks is something I’ve had to sit down and think about; what makes more sense in the processing chain, or in editing. Also, what I title a session, where I save it to, backing it up regularly. I’ve realized the need for maintaining a basic database; a spreadsheet that references where I save sessions and related data, both on the internal hard drive of my computer, and on external drives.

In learning to be organized, I’ve slowly begun to realize the value of taking time to ask myself what steps to take, in the moment, to be sure I can retrace those steps later on.

Last but not least…

Maybe most importantly, this capstone completion process helped me crystalize a mentality for success. I worked in a proper studio, on professional equipment, with a large group of musicians, and got a solid result that I’m happy to put my name to. It’s given me the confidence to dig in and do it all again, except better next time. That experience alone made this degree invaluable. Thank you, TSU! Thank you Gary, Mark, Billy, Chris, and Michele! I love you guys!